The Lambda Calculus for Absolute Dummies (like myself)

If there is one highly underrated concept in philosophy today, it is computation. Why is it so important? Because computationalism is the new mechanism. For millennia, philosophers have struggled when they wanted to express or doubt that the universe can be explained in a mechanical way, because it is so difficult to explain what a machine is, and what it is not. The term computation does just this: it defines exactly what machines can do, and what not. If the universe/the mind/the brain/bunnies/God is explicable in a mechanical way, then it is a computer, and vice versa.

Unfortunately, most people outside of programming and computer science don’t know exactly what computation means. Many may have heard of Turing Machines, but these things tend to do more harm than good, because they leave strong intuitions of moving wheels and tapes, instead of what it really does: embodying the nature of computation.

The Lambda Calculus does exactly the same thing, but without wheels to cloud your vision. It might look frighteningly mathematical from a distance (it has a greek letter in it, after all!), so nobody outside of academic computer science tends to look at it, but it is unbelievably easy to understand. And if you understood it, you might end up with a much better intuition of computation.

The Lambda Calculus has been invented at roughly the same time as the Turing Machine (mid-1930ies), by Alonzo Church. Don’t be intimidated by the word “calculus”! It does not have any complicated formulae or operations. All it ever does is taking a line of letters (or symbols), and performing a little cut and paste operation on it. As you will see, the Lambda Calculus can compute everything that can be computed, just with a very simple cut and paste.

A line of symbols is called an expression. It might look like this: (λx.xy) (ab)

We only have the following symbols:

- Single letters (like

a, b, c, d…), which are called variables. An expression can be a single letter, or several letters in a row. More generally, we can write any two or more expressions together to get another expression. - Parentheses:

( ). Parentheses can be used to indicate that some part of an expression belongs together (just as the braces around this part of the sentence make it belong together). Where we don’t have parentheses, we look at expressions simply from left to right. - The greek letter

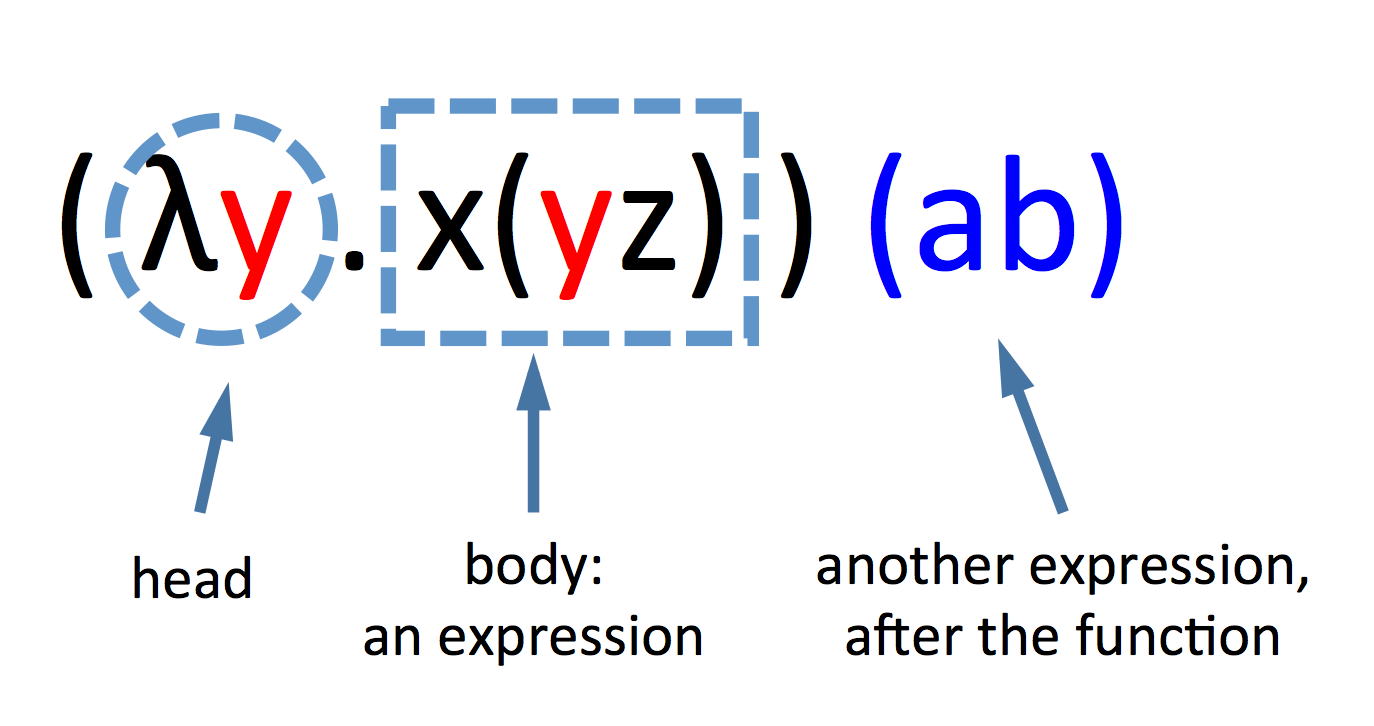

λ(pronounced, of course: Lambda), and the dot:.Withλand the dot, we can write functions. A function starts always with theλand a variable, followed by a dot, and then comes an expression. Theλdoes not have any complicated meaning: it just says that a function starts here. Theλ-variable-.part of a function is called its head, and the remainder (the expression) is called the body.

Q: What is the value or meaning of a variable?

A: None. Variables do not stand for anything. They are just empty names. Even the name is unimportant. The only thing that matters is: when two variables have the same name, they are the same. You can rename variables all you want, without changing the expression.

Q: What does a function calculate?

A: Nothing, really. It is just a kind of expression, with a head and a body. It just stands there. The only thing we can do with it is to resolve it.

Q: Why “

λ”?A: An accident, perhaps. Initially, Alonzo Church just drew a little roof to mark the head variable, like this:

(ŷ xy) ab. In the typed manuscript, he put the roof in front of the head, so it became(⋀y.xy) ab. The typesetter turned it into(λy.xy) ab, which is visually close enough.

Slightly more formally, we can say: All variables are lambda terms (a valid expression in the lambda calculus). If x and y are lambda terms, then (x y) is a lambda term, and (λx.y) is a lambda term. From these three rules, we can construct all valid expressions. If we also agree to read all lambda expressions from left to right, we can omit a few of the parenthesis: (λy.xy) ab is the simplified version of (((λy.(x y)) a) b).

Cut & Paste

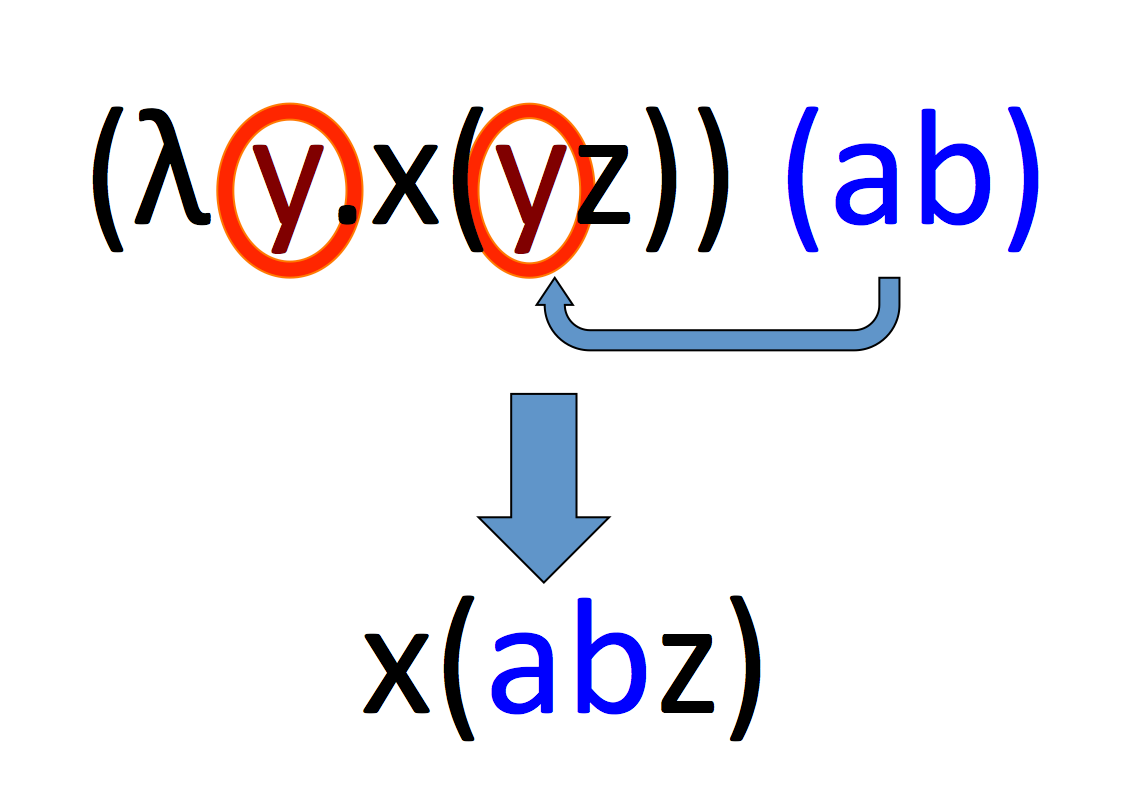

Functions can be resolved if they are followed by another expression. The resolution works by taking the variable mentioned in the head, and replacing all of its occurrences within the body with the expression after the function. We cut the expression after the function, and paste it into the body, in every place indicated by the head. Having done that, we throw the head away, because it has served its purpose: telling us which variable to replace.

The resolution of functions is the only thing we can ever do in the Lambda Calculus. Once we have gotten rid of all the lambdas, or if there are no more expressions after the remaining functions, we cannot replace anything any more. We can go home now.

Q: Can functions contain other functions?

A: Absolutely. Functions are expressions, and expressions can contain other expressions, so functions can be parts of the bodies of other functions, or be part of the replacing expression. In fact, we have expressions like

λx.λy.xzyso often that we like to abbreviate them asλxy.xzy. This means that we will try to replace the first variable in the head (x) with the first expression after the body (xzy), the second variable (y) with the next one after that, and so on.

The variables mentioned in the head (the one tagged for replacement) are called bound variables. Unmentioned variables are free variables. Because functions can be part of other functions, a variable may be both bound and free in the same expression.

Q: I find this a little bit confusing.

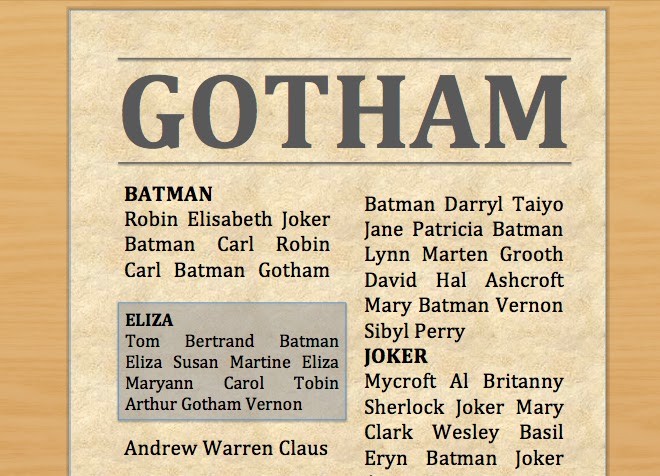

A: Think of it like this: Imagine you are editing a very minimalist gossip newspaper. Everything the newspaper writes about, ever, are names (we don’t have articles, verbs, pronouns–just names). People don’t want to be recognized in your paper, and you anonymize them by replacing all names with arbitrary pseudonyms. So, the names do not mean anything, but if two names in the same text are the same, they refer to the same person.

All text in the newspaper is arranged in text blocks. A text block is ultimately made up of nothing but names, and it may have a headline, but does not have to. Headlines are printed in bold face, and consist of a single name. All occurrences of that name within the text belonging to the headline are famous, that is, they refer to that headline person. All names that are not headline material are ordinary. Text blocks may contain other text blocks, including their headings (which work like sub-headings, or sub-sub-headings and so on). Thus, a name may be ordinary in one sub-text, but in another, it may be made famous by the headline of that sub-text.

This is exactly like the Lambda Calculus: names are variables, text blocks are expressions, and headlines are function heads, only instead of being printed in bold, they are surrounded by a λ and a dot, so we know where they begin and end.

The resolution operation is a simple find/replace operation. We find all occurrences of the bound name in a headlined text block, and replace each of them with the following text block. (However, note that replacing names by whole paragraphs etc. rarely makes sense for real newspapers.)

By the way: we might run into a little problem if the replacing text contains names that are also mentioned in the original text that we merge it into. All names are anonymized pseudonyms, but we could have used the same pseudonym for different people in different texts. If we combine these texts now, we must make sure that different people are referred to by different pseudonyms, so perhaps we have to rename some of them.

Alternatively, we might insist that no two text blocks use the same names. (In other words: either use different variables in unrelated expressions, or make sure you do not forget to rename them during the replace operation as necessary.)

Q: What happens if a variable is bound in the head of a function, but does not occur in the body?

A: The variable is bound, of course. But during replacement, the replacing expression will simply disappear, as there are no places where it could be inserted. That is ok, really: it simplifies our result, so what is not to like?

Numbers

With all the technicalities out of the way (yay! that was easy, wasn’t it?), lets see what nice tricks we can do with the Lambda Calculus. You might argue that computation should be able to do things with numbers, so let us build some. Mathematicians often like to start with natural numbers, and then go from there, by defining all sorts of operations that give us other the other number types.

The easiest way of defining all natural numbers at once works by first defining the first one (which is zero), and a successor operation. By using the successor operation on any natural number, we get another, bigger natural number, and so we can derive them all by counting forward.

Let us express zero as:

0 :⇔ λ sz.z

(Remember: this is shorthand for λs.λz.z, and it means exactly the same thing as λab.b, or λqx.x.) This expression has an interesting property: when resolved, it will throw away the first expression after it, and keep the second one intact. The bound variable s will be replaced by nothing (it does not occur in the body), and the variable z by itself.

Similary, we can use:

1 = λ sz.s(z)

2 = λ sz.s(s(z))

3 = λ sz.s(s(s(z)))

4 = λ sz.s(s(s(s(z))))

...

In other words, our number notation works by nesting the expression s(…) around our z as often as the number says (which also means: if we resolve the number n, it will replicate the following expression n times). We can also say: we apply s n times to z.

A nice successor function is

S :⇔ λ abc.b(abc)

Let us calculate the successor of 0 with it:

S0 = (λ abc.b(abc)) (λ sz.z)

= λ bc.b((λ sz.z) bc)

= λ bc.b((λ z.z) c)

= λ bc.b(c)

This last expression cannot be simplified any further (no more expressions follow the function body), and, surprise!–

λ bc.b(c) = λ sz.s(z) = 1

In other words, the successor function, when applied to our notation of 0, will yield the notation for 1. Can we do it again?

S1 = (λ abc.b(abc)) (λ sz.s(z))

= λ bc.b((λ sz.s(z)) bc)

= λ bc.b((λ z.b(z)) c)

= λ bc.b(b(c))

and lo! and behold:

λ bc.b(b(c)) = λ sz.s(s(z)) = 2

As we see, our successor function does exactly what it is supposed to do: starting from 0, it can produce any natural number. It does this by bracing one more s(…) part around the body of any natural number supplied to it. Ah, the magical powers of cut and paste!

Q: This is a very strange way of writing numbers…

A: Actually, from the point of view of mathematics, this is not stranger than using the characters 1, 2, 3… and so on, or Roman literals (I, II, III, IV, V…), or Chinese ones (一, 二, 三, 四, 五, …), or binary notation (1, 10, 11, 100, 101…). There is no true way of writing numbers, there are only conventions. Natural numbers do not care about how we spell them.

Addition

Adding numbers can be understood as automating the successor function. If we want to add 5 to the number 3, this can be interpreted as using the successor function five times on 3. (Or the other way around, because 3+5 = 5+3.)

Fortunately, our way of writing numbers has this automation already built in. As we have pointed out above, evaluating a number n means that we replicate the expression after it n times. If the expression after it is the successor function, it will be spelled out n times, and if we resolve it, then the successor function will be applied n times to the number expression after it.

3+5 = 3S5 = (λ sz.s(s(s(z)))) (λ abc.b(abc)) (λ xy.x(x(x(x(x(y))))))

If you feel playful, you may try and see that it resolves properly to 8: λ xy.x(x(x(x(x(x(x(x(y)))))))).

Multiplication

A similarly clever function yields multiplication:

MULTIPLY :⇔ λ abc.a(bc)

This function takes two arguments, for instance like this:

2 x 3 = MULTIPLY 2 3 :⇔ (λ abc.a(bc)) (λ sz.s(s(z))) (λ xy.x(x(x(y))))

= λ c.(λ sz.s(s(z)))((λ xy.x(x(x(y))))c)

= λ cz.((λ xy.x(x(x(y))))c)(((λ xy.x(x(x(y))))c)(z))

= λ cz.(λ y.c(c(c(y)))) (c(c(c(z))))

= λ cz.c(c(c(c(c(c(z)))))) = 6

Why does this work? If we look closely, we see that our multiplication function takes its two arguments (2 and 3) and arranges them like this:

MULTIPLY 2 3 = (λ abc.a(bc)) 2 3 = λ c.2(3c)

Resolving this gives us λ cz.(3c)(3c(z)). This is equivalent to applying the second c three times to the z: c(c(c(z))), and applying the first c three times to that result: c(c(c( c(c(c(z))) ))). Together with the function head λ cz, it conveniently results in 6 (i.e., six times the application of the first argument to the second).

The best way to get rid of any remaining bewilderment will be if you take a piece of paper and a pen and try a few multiplications yourself. You will find that you quickly get the hang of it.

Counting Backwards

So far, we have only be going from smaller numbers to larger ones. For subtraction, we might want to have a predecessor operation, too, so we can count backwards. How can we build one

According to our earlier definition, any number is the successor of another one, with the exception of 0, which we just spell out (as λ sz.z). We can use this definition and describe a predecessor as the number that will give us the originally given number by applying the successor operation.

In common Mathematicalese, we could say: y = P(x) ⇔ x = S(y) – that is, y is the predecessor of x if and only if x is the successor of y. Unfortunately, this is only a specification, and not a computation. A specification tells us what conditions the predecessor function must fulfill, but not necessarily how this function works. The Lambda Calculus only does computation, that is, we must tell it exactly and in perfect detail how we can get from x to y.

One possible way of doing that works by starting with 0, and applying the successor function x times:

x S 0 = x (λ abc.b(abc)) (λ sz.z)

The resulting expression will be the numeric value of x. If we could find a way to remember the state of the expression at the x–1st succession (one before the last application of s(…)), we would have the expression for x’s predecessor.

Let us do this by using a pair of numbers. Instead of x, let us use (y, y-1). Then define a successor function that derives (y+1, y) from the pair. We start with setting y at 0, and repeat the application of the successor function x times, after which the pair will have the value (x, x-1). Now select the second half of the pair, and we are done. Here we go: Let us write a pair (a, b) as λp.pab. The smallest possible pair is λp.p00, spelled out as λp.p (λ sz.z) (λuv.v). We can form the successor pair by grabbing the first member, a, and creating a new pair (a+1, a) from it. The first member of a pair λp.pab is given by applying it to to λxy.x.

(λp.p a b) (λxy.x)

= (λxy.x) a b

= (λy.a) b

= a

(As we see, λxy.x preserves the first expression after it, but erases the second. Likewise, the other member of the pair will be selected by λxy.y.) The new pair (a+1, a) can be obtained from a by using the successor function S = λ abc.b(abc) on a, and stuffing S a and a into a new pair.

NEXT-PAIR pair :⇔ (λ pair z.z S (pair λxy.x) pair λxy.x) = (a+1, a)

(Don’t be confused by my use of λ pair. This simply means that the pair (a, a-1) is going to be inserted in the body of the Lambda function.)

Let us now apply this function n times to the starting pair (0, 0), and select the second half of the pair, which will be our final result. You may have noticed that I just cheated a little: (0, 0) is not totally the same as (0, –1), so it is not a sparkling example of a pair (a, a-1). However, we have no negative numbers to work with yet, and for our helper function NEXT-PAIR, it does not make any difference, because it ignores the second half of the pair anyway. Repeated application of NEXT-PAIR on (0, 0) will give us (1, 0), (2, 1), (3, 2), (4, 3) and so on.

P n :⇔ (λn.n NEXT-PAIR(0, 0)) λxy.y

Using the predecessor function P, we can indeed count backwards within the natural numbers. Note that once we reach 0, we will stay at 0, which is probably a good thing. I will leave the definition of negative numbers, division, powers and imaginary numbers as an exercise to the reader. (Well, in seriousness: we could easily fill many pages with the recreation of the standard inventory of set and number theory, but won’t add very much to our basic understanding.)

Q: I can see how we can do subtraction: by applying the predecessor operation multiple times. But every time, we have to go back to 0 and produce all intermediate numbers with the successor operation, just to do a single predecessor operation. Isn’t this very inefficient?

A: Who cares! The Lambda Calculus only claims to effectively compute everything that can be computed–but it does not promise to do it efficiently. (Also, it is a mathematical idea, so it can run at infinite speed in some ephemeral mathematical universe.)

Logic

The Lambda Calculus is not restricted to calculating numbers. It can just as easily compute logical expressions. Remember the two little pair picker functions? We can use these as the definitions of true and false:

TRUE :⇔ λ xy.x

FALSE :⇔ λ xy.y

Boolean Logic uses a few operators, like AND, OR and NOT to determine the value of logical expressions. We can pull this off with the Lambda Calculus, too. For instance, we can negate a TRUE into a FALSE, and a FALSE into a TRUE with

NOT :⇔ λ a.a (λ bc.c) (λ de.d)

How does it work? If we write something like NOT TRUE (spelled out as (λ a.a (λ bc.c) (λ de.d)) λ xy.x), the initial λ a.a will pull the TRUE in front of the expression (λ bc.c) (λ de.d) = FALSE TRUE. Remember that TRUE is the same function we used to pick the first member of a pair, so TRUE FALSE TRUE is the same as: pick the first one of the pair (FALSE, TRUE).

Here are AND and OR; if you like, find out why they work:

AND :⇔ λ ab.ab (λ xy.y)

OR :⇔ λ ab.a (λ xy.x) b

Conditionals

We cannot just compute logical values from other logical values. The following function tells us if a given value is equal to 0. If it is, we get TRUE, and FALSE otherwise. Such a test is very useful when writing programs.

IS-ZERO :⇔ λ a.a FALSE NOT FALSE

If we apply IS-ZERO to any value n, we get

IS-ZERO n = n FALSE NOT FALSE

This will apply the function FALSE n times to the function NOT, and the result to the remaining FALSE. The each time, the first FALSE (= λ xy.y) erases the expression directly after it. Eventually (after n times) it gets to NOT FALSE, erases the NOT and returns the FALSE. Thus, the result of IS-ZERO n is always FALSE. (If you find this confusing, try an example.)

The only exception is when n = 0. If we apply 0 to FALSE NOT FALSE, it will erase the first expression, and only NOT FALSE = TRUE remains:

IS-ZERO 0

= (λ sz.z) FALSE NOT FALSE

= NOT FALSE

= TRUE

Now that we know if a number is 0, we can find out if one number is greater than or equal to (≥) another:

GREATER-OR-EQUAL n m :⇔ λ n m. IS-ZERO(n P m)

In other words, we perform n times the predecessor function on m. If n is exactly the same number as m, the result will be 0, and if n is greater than m, the result will still be 0. Only if m is greater than n, the result will be non-zero.

Using ≥, we can also determine equality: n = m, if n ≥ m and m ≥ n. We can express this directly now:

EQUAL n m :⇔ λ n m. AND (GREATER-OR-EQUAL(n m) GREATER-OR-EQUAL(m n))

= λ n m. AND (IS-ZERO(n P m) IS-ZERO(m P n))

Furthermore…

As you see, the Lambda Calculus is a (minimalist) programming language. As it must be, since every possible computer program can ultimately be mapped into a Lambda function. In fact, the venerable and powerful programming language Lisp has been built directly on the idea of the Lambda calculus, mainly by tweaking the syntax in useful ways, formalizing the creation of function macros and adding a few practical data types.

Our little introduction is loosely based on Raúl Rojas’ excellent Tutorial Introduction to the Lambda Calculus, which also covers recursion and is overall slightly more technical, since it addresses students of Computer Science. Also, using your new-found understanding, you might now go and battle your way through more advanced introductions, such as the one given on Wikipedia.

Everything that is computable

The Lambda Calculus cannot do all of mathematics, because many mathematical problems have no solution, and many mathematical formulas cannot be computed (which is not the same thing). So, which one is more powerful, a Turing Machine or the Lambda Calculus? As it turns out, it is always possible to map the inscriptions of the tape of a Turing Machine into an a Lambda expression (that also includes information on the state and position of the read/write head), and construct a Lambda function that changes this expression with exactly the same result as the corresponding Turing Machine.

Conversely, it is possible to map any Lambda expression onto a tape, and construct a Turing Machine that performs all the necessary find/replace operations on it. Thus, it can be proven that Lambda Calculus and Turing Machine have exactly the same power. In the same way, it can be shown that every other computer we can (or could) construct has the same power, too. This includes personal computers, super-computers, quantum computers and even iPhones. The only differences are in practically realized memory sizes, and the number of steps necessary to reach a result. The insight that all computers have fundamentally the same power is called the “Church Turing Thesis”.

The Lambda Calculus can also be used to compute neural networks with arbitrary accuracy, by expressing the strengths of the connections between individual neurons, and the activation values of the neurons as numbers, and by calculating the spreading of activation through the network in very small time steps. Technically, every realizable system that manipulates information is computable, and every computable system that can express the Lambda Calculus (or something else that can express the Lambda Calculus) is a computer.