No, the Universe is not a Brain

At Forbes, Ethan Siegel asks if the universe may be alive. This might bring us to the question what it means to be alive. When biologists started their field, they could only define it by extension (e.g. animals, plants and other similarly animated things), but did not yet have a functional definition of what made the living stuff so special, and came up with vague and wrong ideas (like a motive force, a vis vitalis, permeating living tissue). Now, a few hundred years later, biologists have agreed that they study the class of systems that are organized into one or more cells and self-organize and stabilize based on information stored in DNA. By that definition, the universe is quite certainly not alive.

However, Ethan Siegel (and a few others, like Bernardo Kastrup) suspect that the universe might be conscious, i.e. that the structure given by its stars, galaxies and galaxy clusters might lend itself to a giant information processing architecture.

Arguably, the field of cognitive science is still comparable to early biology when it comes to defining its object of study: researchers somewhat agree that higher mammals, birds and octopi have minds, cognition, a degree of intelligence and awareness, but we do not have a universally accepted functional definition of these properties. Fortunately, cognitive scientists have discarded the vis vitalis equivalent of the mind: the soul, and most of them will agree that minds are motivated information processing systems that make sense of their environment. In a biological organism, this information processing is facilitated by the exchange of signals between different types of neurons and possibly involving glia cells, by means of electrical impulses and chemicals that either act on large portions of the nervous system, or locally at the interface between individual neurons.

It is not clear what environment our universe should make sense of, but contemporary physics tells us something about the limits of its information processing.

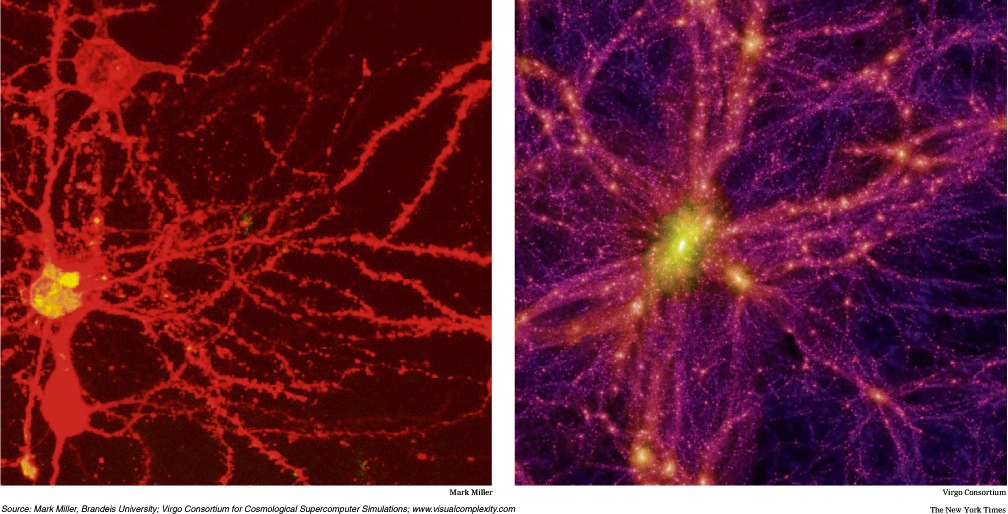

Both Siegel and Kastrup (and Clifford Pickover, and oh well, you know who you are) like to illustrate their arguments with the following image:

This image sends a clear message: if we squint a little, then a well-chosen cutout of a false colored image of a golgi stained pyramidal neuron will look like a red down feather, and a well-chosen cutout of a differently false colored galaxy cluster also looks like a purple down feather, and therefore it is extremely likely that the universe is a giant brain.

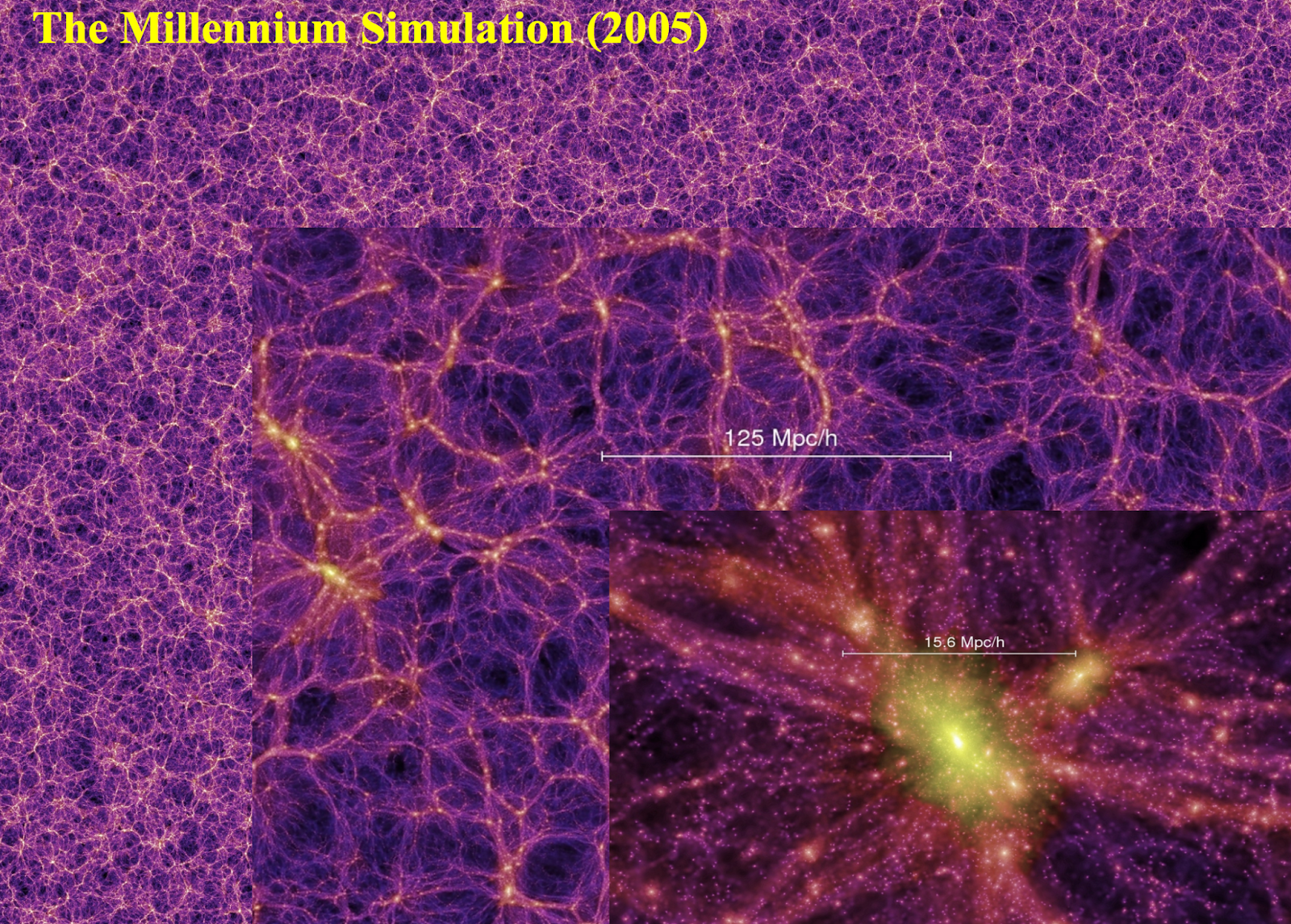

The latter image is a small portion of a computer generated impression of a part of our universe:

At the largest size, Google image search tells me that it looks exactly like foam rubber. Foam rubber is created by combining a chemical agent that glomps together through the wonder of polymerization with another chemical agent that delivers lots of gas bubbles to make space between the polymers. Universes are created by rapidly expanding a superdense plasma that glomps together through the wonders of gravity, while lots of expanding vacuum makes space between the galaxy clusters. Brains totally do not look like foam rubber, because the space between the neurons is filled by other neurons and glia cells and protein sheaths that were all not visible in the selectively stained image above, and also because the cortical surface is stacked into four to six layers that are altogether just a few dozen neurons high.

Neurons are pretty slow and it takes about 200ms for a stimulus applied directly to a sensory area of the cortical surface to raise towards awareness. In that time, signals pass back and forth multiple times through the entire length of the cortex, via a path of highly specifically selected neurons, until a global cortical pattern involving a distinct grouping of distant regions stabilizes, and is scooped by the attentional circuits in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Building these pathways takes the brain several months, both before and after birth, during which the cortical structure adapts to the statistics of the sensory stimuli of the environment.

If the neurons of the universe were indeed galaxy clusters, their speed of transmission would be limited to the speed of light, which means that sending a signal from one multigalactic neuron to its immediate neighbor would take in the order of a hundred million years. In the 13 billion years since the formation of the first galaxies, a signal would not have traveled further than a few hundred adjacent galaxies, i.e. much less than a millimeter of equivalent distance in the neocortex. It is pretty safe to say that the galaxy cluster brain will not have enough time to become aware of anything before burnt out stars and interstellar expansion will destroy any likeness to purple foam rubber.

What does the situation look like if we could convince individual stars to act as neurons, and limit our interstellar brain to the size of a single galaxy? Within our galaxy, stars tend to be only a few light years apart, and it conveniently contains a similar number of stars as our brain has neurons (100 million). A signal could travel a hundred thousand times from one edge of the galaxy to the other before most of the stars burn out, perhaps an equivalent of several minutes of brain activity. However, a few minutes will not be enough for the galaxy to establish any structural pathways that would give rise to a cognitive architecture. Since there is no time for the galactic network to self-organize into a brain-like information processor, this would likely require the intervention of a creator god. Said god would have to do that using relatively unstructured balls of plasma that are basically just interstellar dust pulled together by the indiscriminating force of gravity, whereas neurons are highly evolved information processing units with complex infrastructure for internal and external metabolism to produce various specialized signaling compounds that are exchanged and detected with sophisticated machinery embedded into cellular membranes. Even then, the result would be limited to a few moments of awareness.

We have strong reasons to suspect that our universe does not harbor any natural intelligent structures larger than a planet, and since planets do not tend to have very interesting environments to become aware of nor any known mechanisms to evolve mind-supporting information processing structures, the most interesting minds are likely going to be in the service of lifeforms.