The Lambda Calculus for Absolute Dummies

(like myself)

If there is one highly underrated concept in philosophy today, it is computation. Why is it so important? Because computationalism is the new mechanism. For millennia, philosophers have struggled when they wanted to express or doubt that the universe can be explained in a mechanical way, because it is so difficult to explain what a machine is, and what it is not. The term computation does just this: it defines exactly what machines can do, and what not. If the universe/the mind/the brain/bunnies/God is explicable in a mechanical way, then it is a computer, and vice versa.

Unfortunately, most people outside of programming and computer science don’t know exactly what computation means. Many may have heard of Turing Machines, but these things tend to do more harm than good, because they leave strong intuitions of moving wheels and tapes, instead of what it really does: embodying the nature of computation.

The Lambda Calculus does exactly the same thing, but without wheels to cloud your vision. It might look frighteningly mathematical from a distance (it has a greek letter in it, after all!), so nobody outside of academic computer science tends to look at it, but it is unbelievably easy to understand. And if you understood it, you might end up with a much better intuition of computation.

The Lambda Calculus has been invented at roughly the same time as the Turing Machine (mid-1930ies), by Alonzo Church. Don’t be intimidated by the word “calculus”! It does not have any complicated formulae or operations. All it ever does is taking a line of letters (or symbols), and performing a little cut and paste operation on it. As you will see, the Lambda Calculus can compute everything that can be computed, just with a very simple cut and paste.

A line of symbols is called an expression. It might look like this: (λx.xy) (ab)

We only have the following symbols:

- Single letters (like

a, b, c, d…), which are called variables. An expression can be a single letter, or several letters in a row. More generally, we can write any two or more expressions together to get another expression. - Parentheses:

( ). Parentheses can be used to indicate that some part of an expression belongs together (just as the braces around this part of the sentence make it belong together). Where we don’t have parentheses, we look at expressions simply from left to right. - The greek letter

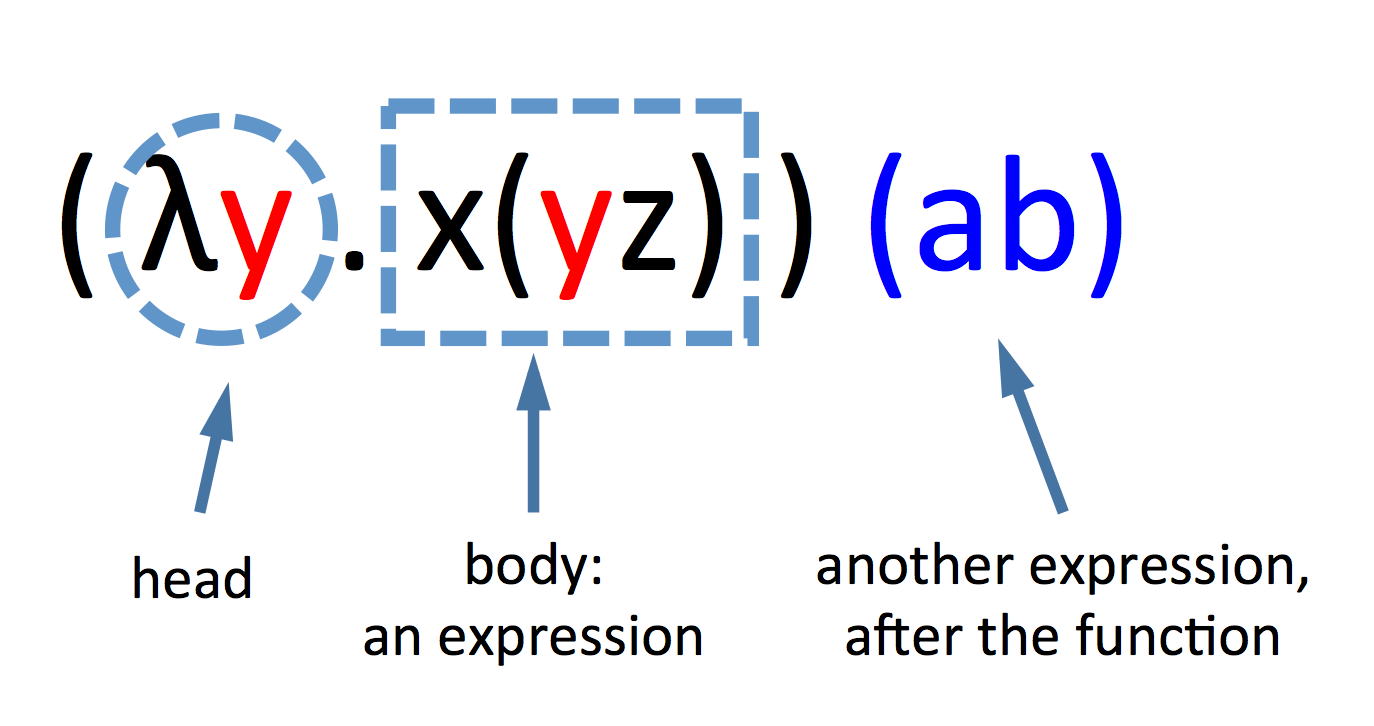

λ(pronounced, of course: Lambda), and the dot:.Withλand the dot, we can write functions. A function starts always with theλand a variable, followed by a dot, and then comes an expression. Theλdoes not have any complicated meaning: it just says that a function starts here. Theλ-variable-.part of a function is called its head, and the remainder (the expression) is called the body.

Q: Why “

λ”?A: An accident, perhaps. Initially, Alonzo Church just drew a little roof to mark the head variable, like this:

(ŷ xy) ab. In the typed manuscript, he put the roof in front of the head, so it became(⋀y.xy) ab. The typesetter turned it into(λy.xy) ab, which is visually close enough.

Slightly more formally, we can say: All variables are lambda terms (a valid expression in the lambda calculus). If x and y are lambda terms, then (x y) is a lambda term, and (λx.y) is a lambda term. From these three rules, we can construct all valid expressions. If we also agree to read all lambda expressions from left to right, we can omit a few of the parenthesis: (λy.xy) ab is the simplified version of (((λy.(x y)) a) b).{: .box}

Cut & Paste

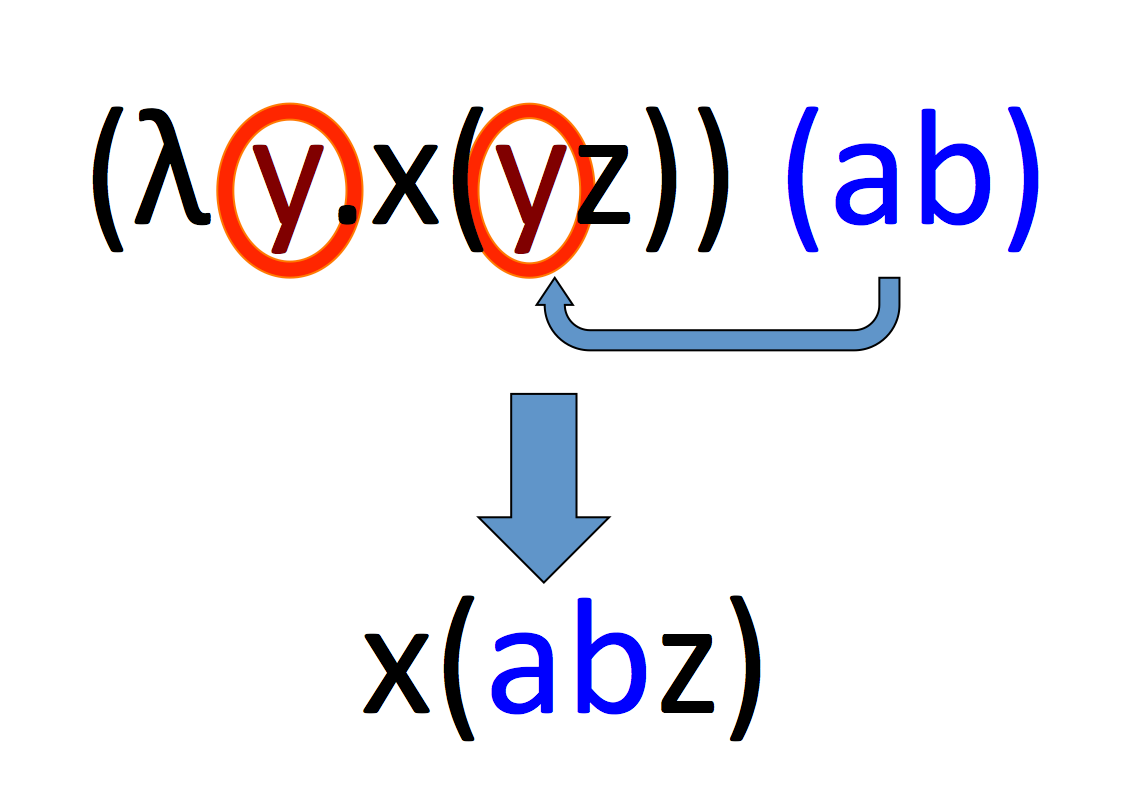

Functions can be resolved if they are followed by another expression. The resolution works by taking the variable mentioned in the head, and replacing all of its occurrences within the body with the expression after the function.1 Having done that, we throw the head away, because it has served its purpose: telling us which variable to replace.

The resolution of functions is the only thing we can ever do in the Lambda Calculus. Once we have gotten rid of all the lambdas, or if there are no more expressions after the remaining functions, we cannot replace anything any more. We can go home now.

Q: Can functions contain other functions?

A: Absolutely. Functions are expressions, and expressions can contain other expressions, so functions can be parts of the bodies of other functions, or be part of the replacing expression. In fact, we have expressions like

λx.λy.xzyso often that we like to abbreviate them asλxy.xzy. This means that we will try to replace the first variable in the head (x) with the first expression after the body (xzy), the second variable (y) with the next one after that, and so on.

The variables mentioned in the head (the one tagged for replacement) are called bound variables. Unmentioned variables are free variables. Because functions can be part of other functions, a variable may be both bound and free in the same expression.

Q: I find this a little bit confusing.

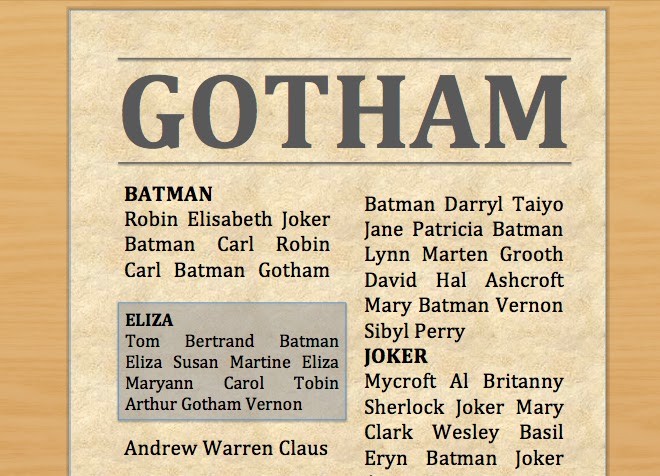

A: Think of it like this: Imagine you are editing a very minimalist gossip newspaper. Everything the newspaper writes about, ever, are names (we don’t have articles, verbs, pronouns–just names). People don’t want to be recognized in your paper, and you anonymize them by replacing all names with arbitrary pseudonyms. So, the names do not mean anything, but if two names in the same text are the same, they refer to the same person.

All text in the newspaper is arranged in text blocks. A text block is ultimately made up of nothing but names, and it may have a headline, but does not2 have to. All names that are not headline material are ordinary. Text blocks may contain other text blocks, including their headings (which work like sub-headings, or sub-sub-headings and so on). Thus, a name may be ordinary in one sub-text, but in another, it may be made famous by the headline of that sub-text.

This is exactly like the Lambda Calculus: names are variables, text blocks are expressions, and headlines are function heads, only instead of being printed in bold, they are surrounded by a λ and a dot, so we know where they begin and end.

The resolution operation is a simple find/replace operation. We find all occurrences of the bound name in a headlined text block, and replace each of them with the following text block. (However, note that replacing names by whole paragraphs etc. rarely makes sense for real newspapers.)

By the way: we might run into a little problem if the replacing text contains names that are also mentioned in the original text that we merge it into. All names are anonymized pseudonyms, but we could have used the same pseudonym for different people in different texts. If we combine these texts now, we must make sure that different people are referred to by different pseudonyms, so perhaps we have to rename some of them.

Alternatively, we might insist that no two text blocks use the same names. (In other words: either use different variables in unrelated expressions, or make sure you do not forget to rename them during the replace operation as necessary.)

Numbers

With all the technicalities out of the way (yay! that was easy, wasn’t it?), lets see what nice tricks we can do with the Lambda Calculus. You might argue that computation should be able to do things with numbers, so let us build some. Mathematicians often like to start with natural numbers, and then go from there, by defining all sorts of operations that give us other the other number types.

Let us express zero as:

0 :⇔ λ sz.z

(Remember: this is shorthand for λs.λz.z, and it means exactly the same thing as λab.b, or λqx.x.) This expression has an interesting property: when resolved, it will throw away the first expression after it, and keep the second one intact. The bound variable s will be replaced by nothing (it does not occur in the body), and the variable z by itself.

Similary, we can use:

1 = λ sz.s(z)

2 = λ sz.s(s(z))

3 = λ sz.s(s(s(z)))

4 = λ sz.s(s(s(s(z))))

...

In other words, our number notation works by nesting the expression s(…) around our z as often as the number says (which also means: if we resolve the number n, it will replicate the following expression n times). We can also say: we apply s n times to z.

A nice successor function is

S :⇔ λ abc.b(abc)

Let us calculate the successor of 0 with it:

S0 = (λ abc.b(abc)) (λ sz.z)

= λ bc.b((λ sz.z) bc)

= λ bc.b((λ z.z) c)

= λ bc.b(c)

This last expression cannot be simplified any further (no more expressions follow the function body), and, surprise!–

λ bc.b(c) = λ sz.s(z) = 1

In other words, the successor function, when applied to our notation of 0, will yield the notation for 1. Can we do it again?

S1 = (λ abc.b(abc)) (λ sz.s(z))

= λ bc.b((λ sz.s(z)) bc)

= λ bc.b((λ z.b(z)) c)

= λ bc.b(b(c))

and lo! and behold:

λ bc.b(b(c)) = λ sz.s(s(z)) = 2

As we see, our successor function does exactly what it is supposed to do: starting from 0, it can produce any natural number. It does this by bracing one more s(…) part around the body of any natural number supplied to it. Ah, the magical powers of cut and paste!

Q: This is a very strange way of writing numbers…

A: Actually, from the point of view of mathematics, this is not stranger than using the characters 1, 2, 3… and so on, or Roman literals (I, II, III, IV, V…), or Chinese ones (一, 二, 三, 四, 五, …), or binary notation (1, 10, 11, 100, 101…). There is no true way of writing numbers, there are only conventions. Natural numbers do not care about how we spell them.

Addition

Adding numbers can be understood as automating the successor function. If we want to add 5 to the number 3, this can be interpreted as using the successor function five times on 3. (Or the other way around, because 3+5 = 5+3.)

Multiplication

A similarly clever function yields multiplication:

MULTIPLY :⇔ λ abc.a(bc)

Our little introduction is loosely based on Raúl Rojas’ excellent Tutorial Introduction to the Lambda Calculus, which also covers recursion and is overall slightly more technical, since it addresses students of Computer Science. Also, using your new-found understanding, you might now go and battle your way through more advanced introductions, such as the one given on Wikipedia.

We cut the expression after the function, and paste it into the body, in every place indicated by the head. ↩

Headlines are printed in bold face, and consist of a single name. All occurrences of that name within the text belonging to the headline are famous, that is, they refer to that headline person. ↩